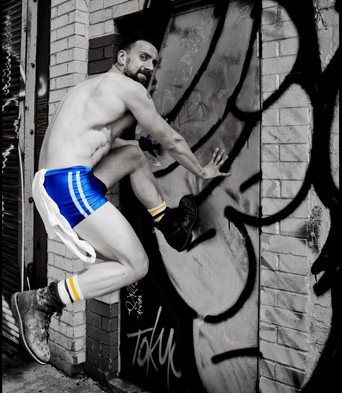

Brendan Healy

ALUMNUS PROFILE

Brendan Healy is the Artistic Director of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre (Toronto). He directed PIG, by Tim Luscombe, directed by Brendan Healy (Directing, 2005), at BBT, from September 14 to October 6, 2013.

This interview was conducted in October 2009, when he was at the NTS to direct the 3rd year Acting students’ production of _Liliom, by Ferenc Molnar.

Photo: inkedKenny, from website of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre_

What lessons did you learn at the NTS that continue to nurture your artistic process today?

A. The School taught me a couple of important things. On the one hand, it taught me to be very true to myself in terms of a vision, to stick to that vision and be very articulate, clear and perseverant about it. And at the same time, it exposed me to new ideas and challenged me to go beyond what I initially thought was the right choice. I was encouraged to remain flexible in terms of approaches, to stretch myself stylistically.

When did you decide to move from acting towards directing?

A. I had actually done some directing at university, which my teachers encouraged me to pursue; I guess they knew something that I didn’t, at the time! But it took about a year of working as a professional actor for me to realize that acting wasn’t my path. I was acting in a show in Montreal; it was entitled Girls! Girls! Girls!, written by Greg MacArthur and directed by Peter Hinton, and presented as part of the FTA. There, I met a theatre company called the New York City Players. A friendship began and I eventually moved to New York to intern with them. I think that’s when I made the decision to direct. I returned to Canada and moved to Toronto, and haven’t acted since.

Do you miss it?

A. No! Not at all!

However, it must give you deeper insight when directing actors?

A. Yes, but as time goes on, I’m losing my “actor connection” and feel like it’s time for me to take an acting class just to remember what it feels like to be on stage. But yes, when I initially started directing, I definitely directed from an actor’s perspective, although less so now.

What do you enjoy most about directing?

A. I think that what I love about directing is what I love about theatre, which is the collaborative aspect of it. I enjoy the collective experience and effort to realize a text, to penetrate and understand it. I like the collective endeavour of creating poetry on stage. I also like being in the middle of the action, being the one who’s looking at the lights and the sound and the acting and watching it all come together with the set and the costumes. I’m not responsible for “one” thing, I’m responsible for everybody else’s responsibilities. I love that aspect of it, it’s very exciting.

Is there a show that you dream of directing?

A. I don’t know if I have “a” dream show…I have, perhaps, a dream process that would make the many shows I would like to direct all the more dreamlike.

And that process would be one where I’d be working with a company of actors whom I know very well. Ideally, we would have a long history together and we would work on shows for extended periods of time. It would also be a process where an audience could encounter our work at various stages; an on-going dialogue with the audience. The work would somehow always be in evolution and the audience would meet it at whatever juncture we were at when we decide to share it. I also imagine this dream process to be in the countryside somewhere, where life and theatre-making are somehow intertwined and it’s an environment where people’s lives are very much connected to the experience of art-making. It’s an old-fashioned vision of an acting company (such as the one depicted by Mnouchkine in the film, Molière) where the artists have a real commitment to each other as people as well as a commitment to making theatre together. That, to me, seems very dreamlike.

What advice would you give someone just starting their career in theatre?

A. I don’t have any original advice to give, but I will pass on something that Robert Lepage said that really resonated for me. When I was a student at the National Theatre School, Lepage was given the Gascon-Thomas Award. In his acceptance speech, he told the students to not worry about being good, but to worry about being unique. I found that to be so liberating: don’t worry so much about whether you’re good enough and just stay true to your own interests and artistic impulses, and have the blind faith that eventually someone will share that interest. And I can say that that has certainly been the case for me – it’s taken a long time – but it certainly has happened.

Do you think that young artists put undue pressure on themselves to “succeed” and don’t give themselves the time to mature and perfect their craft?

A. I think our culture puts a lot of pressure on us that way: we’re presented with a very specific model of success that isn’t reflected in our reality as theatre artists. Graduating school is not an ending; it’s really just the beginning.

A commitment to the theatre is, I think, a lifelong commitment. It’s impossible to say, “Okay, that show is finished, it’s the perfect show and now I’ll move on.” It’s never finished. You could easily spend your life doing the same show every few years, because there’s always something to learn and that’s the gift of the theatre. And it’s a hard lesson to learn, because we expect results in our culture and we really evaluate our self-worth by a kind of economic and social position that the life of an artist doesn’t give you. There are other ways to measure your success and part of the life lesson is learning how to measure success for yourself.

Samuel Beckett wrote: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” I think that’s such a great way of talking about the process of theatre and the process of living too, since it releases you from all the pre-conceived notions of success – whatever that means – and releases your ego from needing to be defined by something outside of yourself. If you just assume that you’re going to fail, I think your life will be more pleasant!

If you hadn’t gone into theatre, what do you think you would’ve done?

A. My dirty secret is that I went to McGill Law School for a year and a half, during the time I was acting professionally. But I dropped out, because it really did not feel right for me. However, I guess if I weren’t directing, I would have somehow found a way to make a career in law work for me.

Please complete this thought: "If I’d known then what I know now…"

A. I probably would have spent less time worrying about what I thought other people wanted me to be and would have spent more time just being myself. That would apply equally to my professional and personal life.